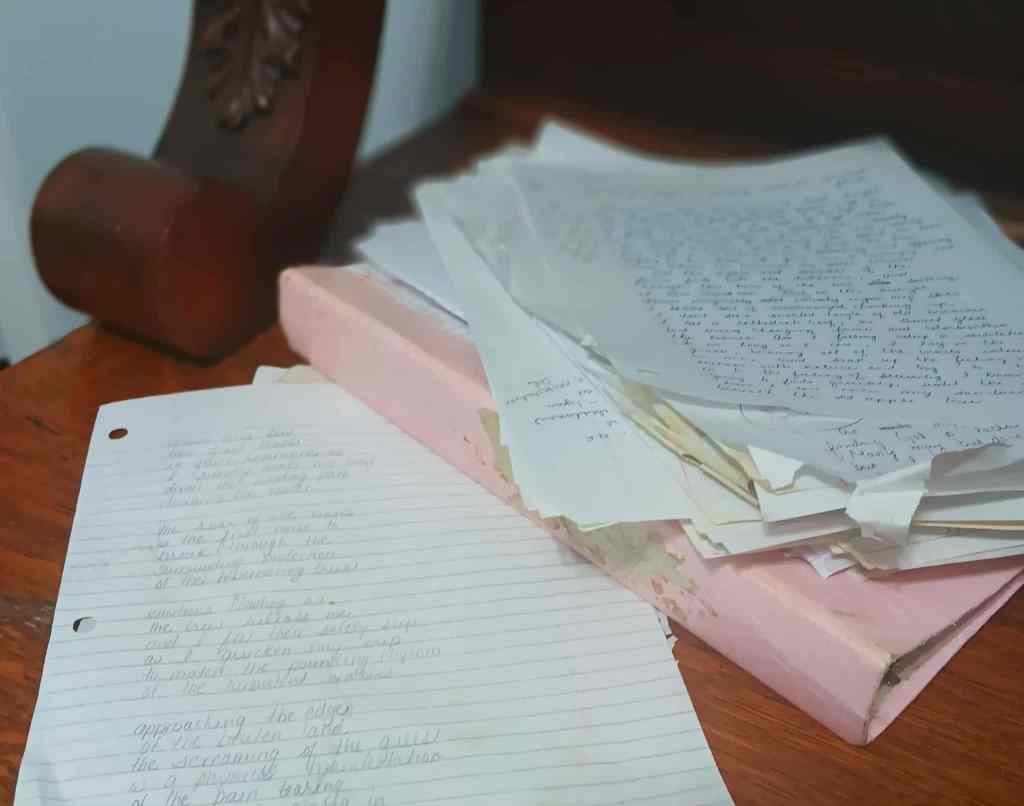

I can’t remember what I was looking for in the boxes in the basement last week. We moved nearly a year ago and most of the packed items remain that way. Last October, when we were packing, I threw away a large amount of things I no longer needed. There were, however, other things I could not bear to part with as they had a connection to my daughter. Or, my boys when they were small. And, to my surprise (and delight) there was a pink hard covered binder that I thought I had lost years ago. Handwritten words on college ruled paper were crammed inside. Relics of a former life.

On these faded and crumpled sheets were dozens of poems I had written over two decades ago. Before I lost my Becca. Prior to the before and after divide her death caused in our lives.

I was happy I had found them as I thought they had been lost forever. And, in truth, I felt kind of alright with that because they had been written about love. Melancholy musings about love lost pale in comparison to the grief one feels after the death of a child.

Carrying them upstairs I placed them on the small desk next to my bed. I was happy I found them but I wasn’t ready to read them yet. I am not sure why. Part of me felt they did not matter anymore. They were of the past. Another part felt as if they would be silly to me after having been through the things I have experienced. I can remember how much I ached when I wrote them but I didn’t truly know what aching loss was. I let them sit there for a few days. Eyeing them every time I entered my room. I felt embarrassed, somehow. Nearly a week passed before I sat down, took the pink binder into my lap, and opened the cover.

The first poem I read pulled me backward through time. My younger self spilled across the page, desperate, raw, convinced that heartbreak was the deepest wound a body could know.

I saw the heartache everywhere. Page after page carried the same refrain: unloved, unlucky, unwanted. I poured it out with the certainty of someone who believed it was her truth.

The emotions were unfiltered, splashed across the page crudely. Anger, sadness, emptiness—they tumbled out without grace, without restraint. I wasn’t writing poetry so much as carving open wounds onto paper. There was nothing polished about it. Just the desperate scrawl of someone who believed she was unworthy and wanted the world to see her ache.

As I was reading them I thought: oh, I would write this so much differently now. Or, would I even write them at all? I can think of little as profound as losing a child. Surely, writing about romantic love lost is superficial. Yet, there were truths I could see between the written words.

Meaning always seems to reside in the space between.

There was anger. Anger is the flame that kept me moving. It burned at men for not loving me the way I thought I deserved. It burned at myself for being “too much” or “not enough.” But beneath it all, anger was a shield – a way to keep from admitting how much I wanted to be loved but I didn’t understand how.

Sadness is the ache I poured into poems, believing I was destined to be unwanted. It sat heavy in my chest, a familiar companion. Sadness told me the lie was truth and convinced me to keep repeating it.

Loss is not just the end of relationships—it is the empty space I carved out myself. It is love I could not hold, because I didn’t believe it belonged to me. I grieve the men I pushed away, but I also grieve the version of myself who never felt safe enough to stay.

Emptiness is the echo of my uncle’s words: you will never be worth loving. I let that sentence hollow me out, and then I kept filling the hollow with chaos. The chaos felt familiar.

Unworthiness is the thread that tied all the others together. I wore it like a second skin, invisible and suffocating. I believed it so completely that I made it real, even when love stood right in front of me and asked me to trust.

Taken together, these emotions painted the story I lived by.

Between the scrawled lines of heartbreak, I saw the girl who believed she was unloved. I saw the anger, the sadness, the emptiness that poured out of her, unfiltered. But I also saw something else—the way she kept writing, kept trying to name her ache. Even then, she was reaching for love, even if she couldn’t recognize it when it stood in front of her.

The truth is, I was loved. There were men who gave me their full hearts, and I could not stay. I read those poems now and feel the grief of that too—the grief of turning away, the grief of sabotaging love that was real.

The harder truth is this: I was not only hurting, I was hurtful. I was the mean one. I lashed out at men who offered me tenderness, cutting them with words sharper than I care to remember. Destroying all in their path. I turned cold when they needed warmth, distant when they reached for closeness. I sabotaged what could have grown, convincing myself that chaos was safer than vulnerable intimacy.

It shames me to admit this, but it is the truth: I drove away the very love I claimed I longed for. I didn’t understand how to stay, how to rest in gentleness. Meanness became my defense, and I used it every chance I could. Looking back now, I see the cruelty was not born of malice but of fear—the fear that if I let love root itself in me, it would reveal my unworthiness all over again.

I saw myself as the victim. And though there were times I truly was, I also made victims out of others. This is the hardest confession: that pain, when left unspoken, when left unhealed, becomes something we pass on. My cruelty was the echo of wounds I carried from childhood, but it did not feel like an echo to the men who received it. To them, it was sharp, cutting, real.

This is what I regret most—that I repeated what had been done to me, even as I swore I wanted love. That I became the one who hurt, even while drowning in my own pain. That there are some who deserve apologies I won’t ever see again.

The grief I feel at this realization is sharp. But it does not live alone. None of my griefs ever have. They are threaded together, one pulling on the next, like pearls on a single strand.

When I grieve the loss of love—the men I pushed away, the tenderness I couldn’t bear—I feel the weight of losing my daughter too. When I ache for Becca, I also ache for the girl I once was, scribbling poems in pink binders, believing she was unworthy. Each grief stirs the others, until I cannot tell where one ends and the next begins.

This is the truth I have come to see: grief is not separate. It belongs to the same necklace, the same life. To touch one pearl is to feel the whole strand tremble.

And yet, even as the strand trembles, I feel something else. The act of holding one pearl, of turning it gently in my hand, seems to soften the weight of them all. Each grief touches the others, but so does each act of healing.

It is not only sorrow that travels along the necklace. When I polish one pearl with honesty, the others catch the light too. Naming my meanness does not excuse it, but it loosens the knot of silence that held it in place. Weeping for my Becca does not lessen the ache of lost love, but it teaches me how to live with a broken heart and still keep loving.

The necklace is heavy, yes, but it is mine. A whole life strung together: love, loss, regret, tenderness. To carry it is to admit I cannot separate the parts of me. I can only tend to them, one by one, until the strand gleams with all that is unbearable and all that is beautiful too.

I don’t think it’s an accident that I found these poems now. If they had surfaced years ago, I might have rolled my eyes at my own melodrama, or stuffed them back into a box. But now I can read them differently. I can see what I never wrote: the fear, the unworthiness, the deep longing that sat beneath every line. Timing matters. The binder waited until I was ready to face not only the lies I believed, but also the truths I could not see.

Between the lines, I found not just sorrow, but myself.