Reader note: This essay addresses animal injury and end-of-life care.

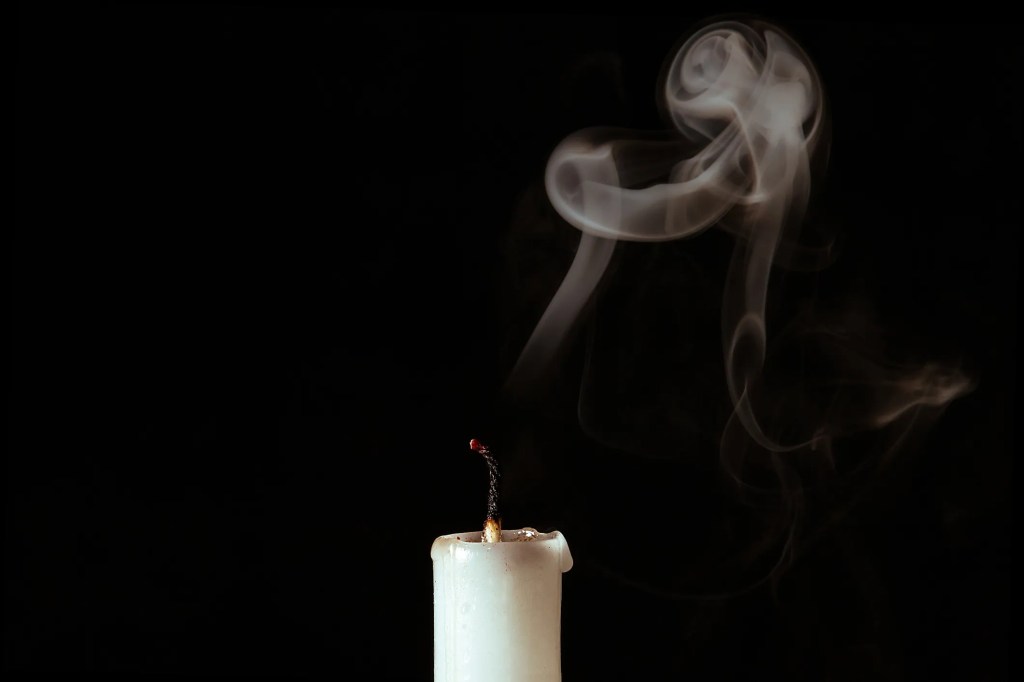

Photograph by the author.

I couldn’t believe what I was seeing—a tiny animal moving near the curb. I swore out loud, because I already knew it wouldn’t end well.

I believe that when you see an animal in need, it becomes your responsibility to respond. You don’t get to turn away. Maybe that’s why dying things find me. Or maybe they’re placed in my path.

Late last summer, during an unbearable heatwave, I was driving home from a long day at the clinic. Sick animals, a euthanasia, broken air conditioning—everything had frayed me thin. I just wanted to go home. I didn’t have the emotional energy to deal with another animal in need. Instead of passing by and doing nothing, I rounded the block and came back.

Before I even reached the street, I saw the remains of a rabbit nest dragged across a freshly mowed strip of lawn between the sidewalk and the road. I was immediately angry. Someone had to have seen it—if not before, then after—and still left its inhabitants scattered and helpless.

Before I could do anything, a crow swooped down, picked up a squirming baby bunny in its beak, and flew into a nearby tree. It settled on a branch beside another crow. I turned away before I had to witness what would happen next. I yelled. I started to cry.

Frantic, I searched the grass and didn’t see any other babies. Then I peered over the edge of the curb into the street, where I’d first noticed movement. One tiny rabbit was still alive, trying to right itself. Afraid the second crow would spot it, I scooped it up and wrapped it in the hem of my scrub top. It was covered in ants. Blood trickled from its nose. Both eyes were missing. I knew it wasn’t going to live.

I could have left it there, or I could take it with me—to the clinic—and help it pass quickly and completely.

I called the vet and told her what had happened. She wasn’t there anymore, but she told me to meet her back at the clinic. The fact that she came back speaks volumes about her integrity.

During the drive, I wailed. I told the baby I was sorry it would never get to live its life. I cried for the one carried away by the crow. I cried for the others I knew must have been in the nest, too.

When I arrived, my coworker had turned on the surgery table so it was warm—maybe comforting. We laid the baby down. The vet examined him. Breathing was labored and uneven. We all knew. She prepared the euthanasia solution and injected it. The three of us stood quietly around the table, hands resting on or near him. Tears fell. We waited. We listened for a heartbeat. He was gone.

My coworker prepared his body for cremation. I didn’t know she’d requested the ashes be returned. When they came back, the label read: Steve — baby bunny. She had cared enough to give him a name. I brought him home.

The bag inside the tin held the smallest amount of ashes I have ever seen. They fit easily into the palm of my hand. They’re still on my dresser, next to my daughter’s ashes. I had planned to scatter the bunny’s ashes under some flowers, but part of me felt I was rushing his life into and out of mine too quickly.

I needed him to exist a little longer.

I had planned to scatter my daughter’s ashes, too. That was always the intention. It’s been nearly twenty years, and I still can’t. I know she isn’t in the urn. I know the rabbit isn’t in the tin. But I can’t. Not yet.

This spring, I plan to buy a flowering bush and plant it over the bunny’s ashes, placing a small stone rabbit nearby. No one else will know he’s there. But I will.

The earth held his body once before, in the nest. It will hold him again. There is something right about that—about returning him to the ground that tried, briefly, to keep him alive.