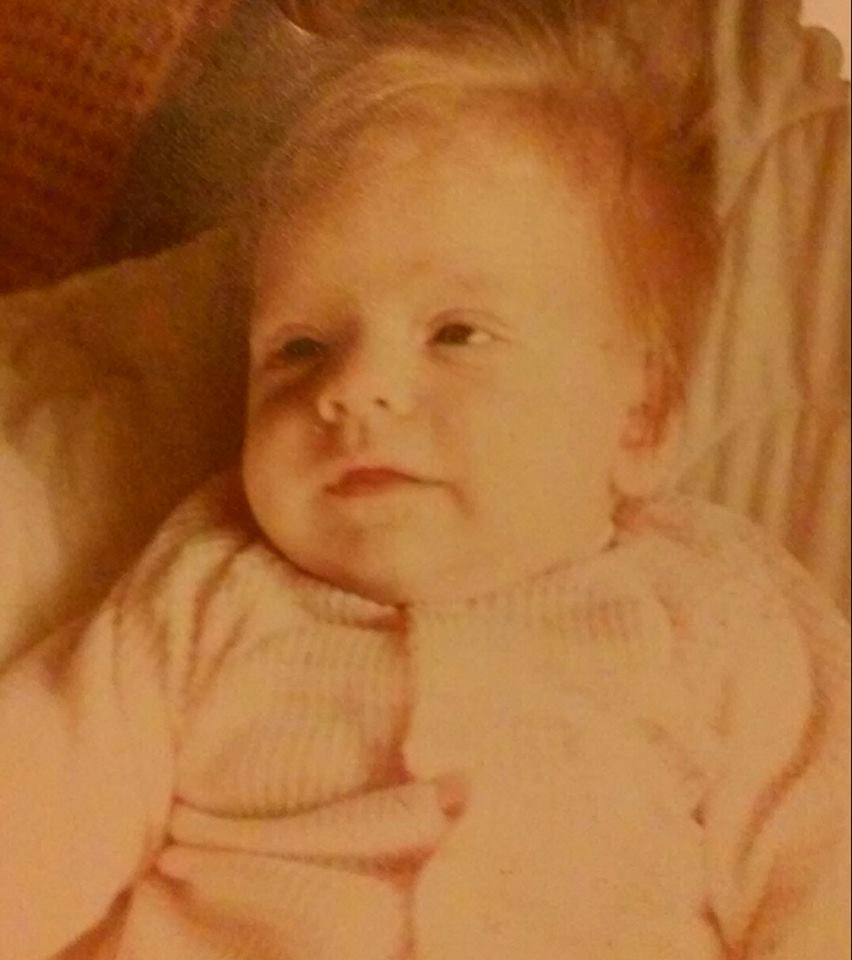

For the past few days I’ve been giving much thought to having a broken heart. Right after Becca was killed I remember thinking “how is my heart still beating? It should just stop.”. Before I lost my daughter I don’t think I ever gave any thought as to whether a person can die from heartache and loss.

According to science, broken heart syndrome is a real condition. Just last year we saw it happen with a famous mother and daughter. The mother died the day after her daughter passed. After reading about the condition, I’ve learned the medical term is: stress induced cardiomyopathy. Women are more likely to suffer from this than men. It’s a reaction to a surge of stress hormones. These facts are clinical. Here’s my truth about a broken heart.

Mine shattered when I was told my daughter was the young woman dead in the body bag. There was “proof” it was her, but I didn’t believe it until a friend came back from seeing her. He told me they unzipped the bag and let him kiss her forehead. She was still warm. Inside of my chest . . . my heart exploded. As I tried to wiggle out of the police officer’s arms, so I could run down to my daughter, my heart beat so wildly and out of time that I thought I might have a heart attack on the same highway where Becca died. There are days, still, when I wish I had.

The thought that our heart physically changes when we lose our child won’t leave me. As if it DID blow apart, but somehow, quickly knitted itself back together enough to keep my body functioning. The pieces reattached to each other, yes, but not arranged the same as before. My heart is different than it was when Becca was alive. I am different. From the smallest cells to the farthest corners of my mind, I’ve been changed.

I also believe I’ve been both weakened and strengthened. I know that sounds odd . . . and makes little sense, but I’ll do my best to explain what I mean.

The cracks in my broken heart have exposed a strength I’m not sure I would have found if not for losing my child. A strength that every single mother gains when she gives birth. The moment we hold our child for the first time, and whether they are with us for an hour or seventy years, we have the truth we could lose them. We don’t often consciously think this thought because it’s too horrifying, isn’t it? Yet, we do know that to love so deeply means we may hurt as deeply someday, too. So, way down inside of our mothers’ hearts, there is a small seed of strength waiting to be called upon if we ever need it. Sadly, some of us do.

When my heart broke wide open and the blood rushed out, so did the combined voices of all the bereaved mothers before me. The lineage of women behind me, cried with me, as I mourned my daughter. I didn’t know it, but I was being lifted by my feminine ancestors. We are held by the hands of those who went before us. Sometimes, in the quiet of the night, I thank them for walking with me during my journey.

All of this being said, personally, I would rather not have found out how strong I really am. I could live without the knowledge that a broken heart can repair itself. That I can march through the days, empty of my Becca, with some hope for my future.

Remember, even when we are alone, we aren’t truly alone. Our hearts can heal. Don’t expect to be the same as “before”. You won’t ever be that person again. The person you become, however, will amaze you.

Let your heart heal. Your child would want you to.