Four months after losing my daughter . . . a woman, who I considered a good friend, called me. The first words that came out of her mouth ended our friendship.

“Are you done crying yet?”

“Are you (a newly bereaved mother) done crying yet (as if four months was enough to mourn my child’s death).”

The word “yet” was a judgement. She made me feel as if I was taking too long and people were getting impatient with me. She was getting impatient with me. She wanted to know if I was finished. I hung up the phone, but the guilt I felt for not being “farther along” stayed with me for a quite some time. I spent so many wasted moments wondering if I was “doing it right”. In truth, I still have those moments, a decade later.

I’ve come to find . . . many bereaved mothers eventually feel as if they are letting others down with their need to grieve. Not only their need . . . but how they grieve, as well.

In the first days, we have no choice but to grieve openly. Our soul’s screams demand to be heard. The intense pain is all encompassing and there is nothing we can do but be in it. There isn’t a way to keep it contained, even if we try, there just isn’t. That kind of anguish can not be controlled. So don’t expect us to do it. If our grief is too much for you then walk away. We don’t need the added weight upon our overburdened shoulders.

As the months pass, and enough people have shown us (or told us outright) that our grief is getting to be “a bit too much”, we learn to hide it. Cover it with a fake smile or a mumbled “I’m alright” when asked how we are doing. We are becoming masters of illusion as to not upset your world. Or, we stop going out as often, not wanting to see the disappointment from others. It’s easier to be alone with the grief. In solitude, we can be who we are. Grieving mothers. Broken and crying.

I wish I could truly convey how I am doing, some days, so you would understand. I know most bereaved mothers, myself included (usually), wouldn’t wish this pain on any one else. But, oh, there are times when I want a callous person to feel what I am feeling.

Do you remember the movie from the mid 90’s, about a young man who is sensitive and other worldly? There is a scene in which the lead character, Powder, uses his supernatural abilities to try to change a man. Powder grabs the arm of a seasoned hunter and shares with him (telepathically) the agony the deer, he’d just shot, was feeling as it died. There are times when I would give nearly anything to have this ability. A way to immediately put someone where I am every day. Just for a moment.

For a long time (months, maybe years) we put on the face society wants to see, and navigate the world in disguise. We go to work, faking it. We participate in holidays, feeling no joy. We laugh, when we really want to cry. We behave in a way that won’t upset those around us. Because, we’ve learned our grief has an expiration date to outsiders. For others, there is a time limit. And for some ungodly reason, many people don’t have a problem telling us so. As my former friend did after just four months of living without my daughter.

The more time that passes . . . the less likely outsiders are to understand why we are still grieving so deeply. Do they think it’s getting easier? I can assure you . . . it isn’t. Does the passage of years somehow soften the pain from losing my child? No, it doesn’t. If anything, it makes it harder. Every dawn brings me farther from the last time I held my daughter.

There is a heaviness added to my spirit with the passing of each day since Becca was killed. A mother with a living child gathers memories along the way . . . as her child lives life. I carry the moments my child never got a chance to live because someone took her life away. How does one ever stop grieving the loss of a child as life unfolds all around us and we are continually, achingly, aware that our child is missing?

A few weeks ago, I had another friend ask me how I was doing. I was honest. I said, “Shitty. Labor day was the last time my entire family was together, so this holiday makes me very sad.” Their reply: “Hasn’t it been ten years? It should be getting easier.”

I can assure you, it isn’t.

If we are lucky . . . we find our voice and can say, with strength, I’ll forever grieve. I generally try to end my writing with something positive to say to the “outsiders”. But, I just don’t have anything tonight. Instead, I’ll end this bit of writing with words for the grieving mothers.

Grieve. Loudly. Or quietly. With your entire being. Don’t worry about what others think. This is your journey, not theirs. Their child didn’t die, yours did. Be pissed at them for not understanding, it’s natural to be angry. Tell them they are wrong. Or tell them nothing. If you can, explain why they are incorrect. If you can’t, don’t worry about it, it’s not your concern. Cry when you must. Scream at the sky. State your truth, whatever it may be, loudly and with courage. Society needs to learn about what child loss grief is and what it isn’t.

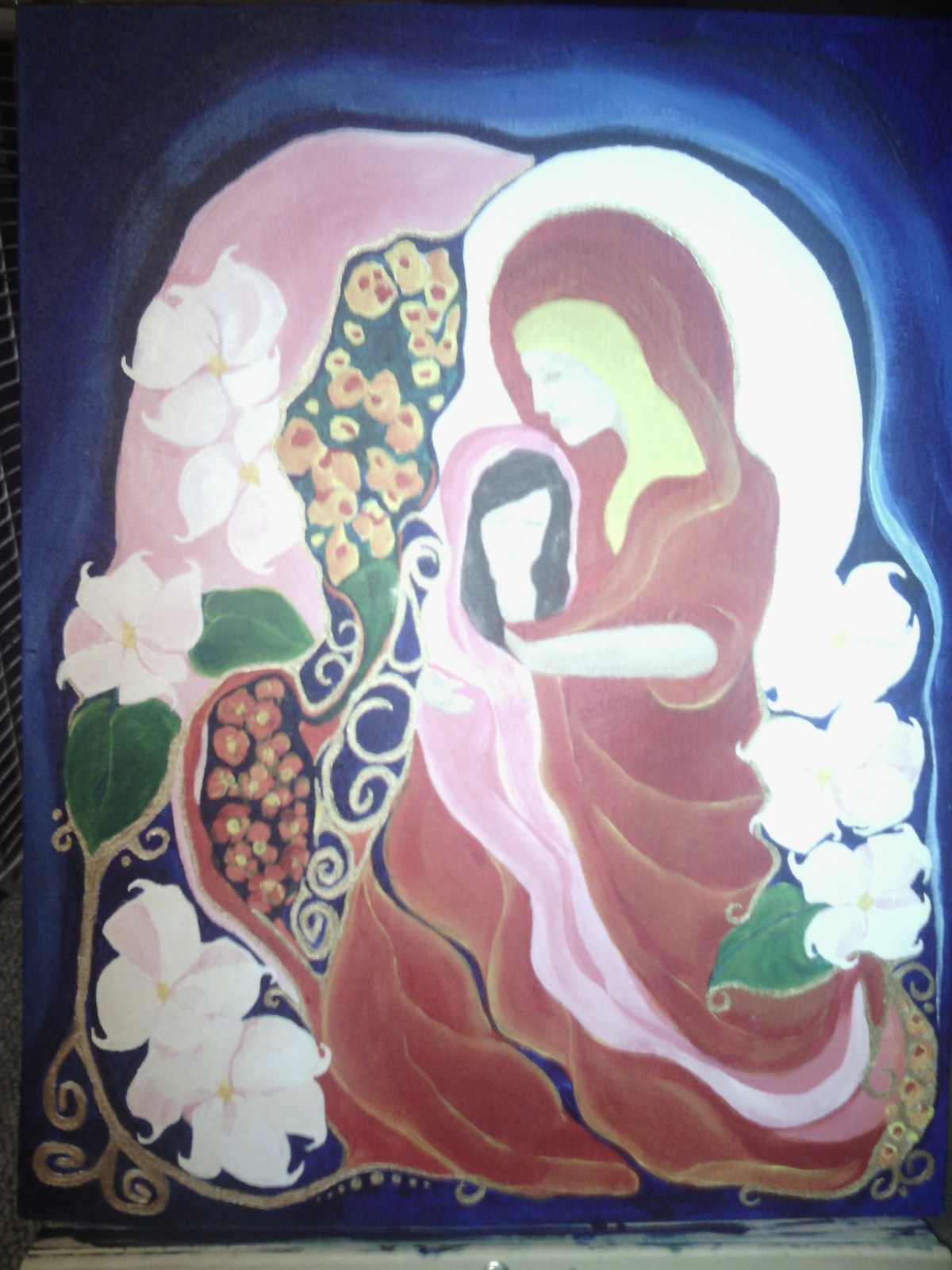

To outsiders, we may look crazed and disheveled. Wild and unkempt. But we don’t care, do we? We are beautiful and pure in our grief. Our pain makes us glow with an inner fire and strength. We have been remade from the inside. Our soul was ripped open and we’ve found the truest parts of ourselves. Make no mistake, though we may seem weak in others eyes, we are stronger than they will ever know. We are warriors and we will lead the way.

When you get to the point in your healing, when you can be authentically who you are at that moment, and you make yourself known to the world . . . you make the path, for the grieving mother behind you, easier to traverse. You change the world.