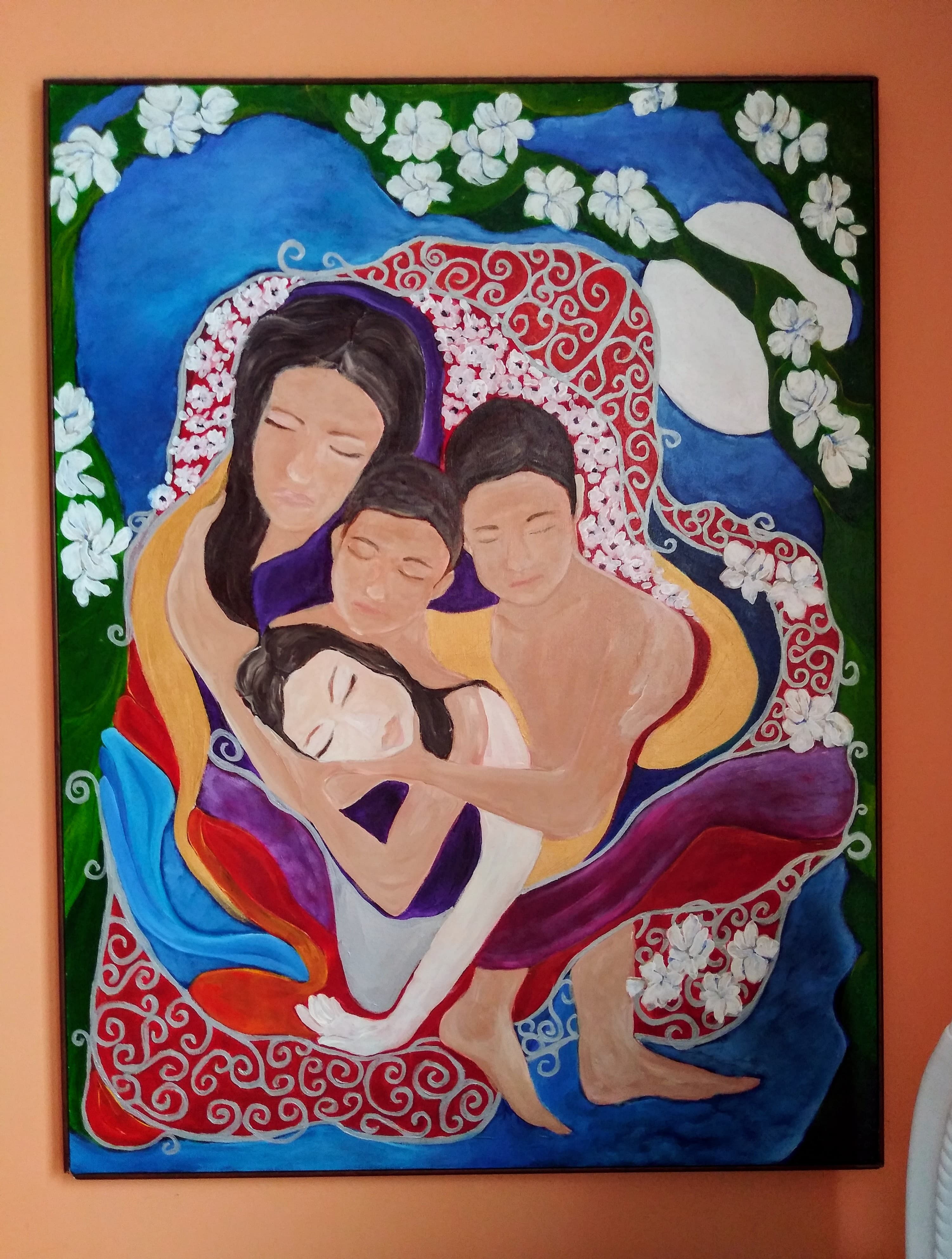

Mothering doesn’t stop after the death of a child. It simply shifts into a kind of prayer. We find a way to carry love beyond the edges of this life.

Their life begins with us in the most intimate way, and sometimes, it ends this way, too. Even when death separates us, nothing can sever the otherworldly tether. Our bodies knew theirs. Our hearts shaped theirs. That intimacy doesn’t end—it just becomes invisible to everyone else.

After she died, my mothering didn’t disappear. It just had nowhere to go.

I didn’t realize this for a long time. That deep need to keep mothering my deceased child was all-consuming. I went from expansive, all-encompassing mothering to the implosion of that care after loss—and the desperate need to put it somewhere.

Before, mothering was in everything: meals, plans, worries, dreams. Death collapses all that vastness. And when it does, the absence doesn’t feel quiet—it feels feral. This can feel like madness. It did for me.

Without knowing I was doing it, I began creating a space where I could still care for my daughter. It started with a simple instinct—the same quiet rhythm I once used to fold her clothes or lay out her favorite books beside her bed. I began gathering things. Placing them near her urn. Not with ceremony, just with care.

Little by little, a kind of altar formed. Not to worship. Not to heal. Just to keep mothering.

In my home, I’ve made a small altar for Becca. It sits on my dresser.

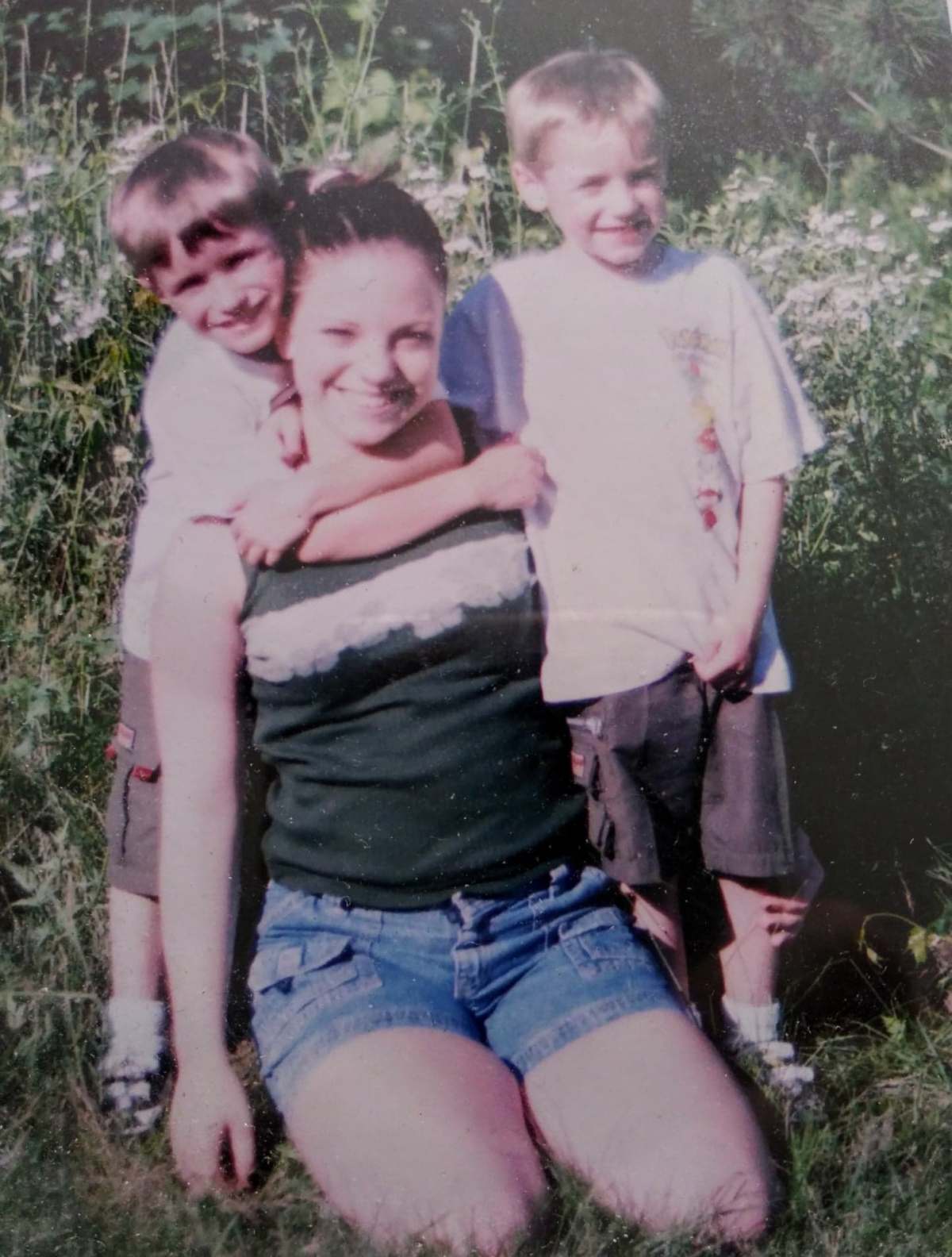

Her urn is marble—cool, smooth, solid. It rests behind a photo of her as a little girl, maybe three years old, with her sweet, mushy lips and soft cheeks. Just looking at it makes my heart skip. Her glasses are nestled at the bottom of the frame. A gift from a friend, the angels on the frame cradle her image like a relic.

To the left is a mason jar filled with fairy lights. I turn them on for her when the nights feel heavy. Behind it stands a white metal statue of a young girl with wings, a bird resting in her hand. My sister gave it to me, saying it reminded her of Becca. We don’t speak anymore, but I’ve kept the statue. Some things still belong.

There’s a peaceful Buddha head that sits nearby—not for religion, but for the sense of calm it offers me when I look at it. On top of her urn is a tiny ladybug house she received as a gift when she was young. Next to that there is a small smooth stone I brought home from Sicily. I know she was there with me.

There’s also a delicate, flower-shaped votive holder. I don’t use it for candles. I tuck inside it the jewelry I’ve been given by my children—gifts from the ones still here, resting beside the one who isn’t.

Behind it, there’s a tiny glass jar filled with cat whiskers. I can’t seem to throw them away. When I find one, I keep it. I don’t fully know why—but it feels like something sacred. Something she’d understand.

This is one of the ways I keep mothering.

I mother through my work, too—through the animals I care for, especially the ones who have been hurt or forgotten. I mother in quiet, invisible ways every day.

But this… this is different.

This is the intimate space between mother and daughter. The one place where I am still doing only for her. No one else. Just her. Just me. Just love that hasn’t stopped.

I’m not the only mother who does this. We all find our own ways to keep mothering.

Some visit their child’s grave weekly, sometimes daily, tending the space as carefully as they once tended their child’s room. I’ve seen mothers kneel beside headstones, gently scrubbing away moss with water and a soft cloth, whispering as they work. Sometimes they lie down on the earth itself—stretching their bodies across the grass, as if to wrap themselves around the child who rests below.

Others return to the place where their child took their last breath—a roadside, a quiet clearing, a stretch of sidewalk—and turn it into a sacred place. Flowers are left. Rocks are painted. Names are written again and again. These places, transformed by love and grief, say: You were here. You mattered. You still do.

These acts may seem small to outsiders. But they are essential. They give us something to hold. Something to clean. Something to protect. A place for our hands to go when our arms are empty.

One does not simply stop being a mother when the child is gone. That’s one of the hardest truths of child loss—we are still mothers, just with no child to mother in the ways the world recognizes.

We are left with silence in the space our child once filled. A silence so loud it can feel like it might break us. And into that silence, we pour what remains of our care. We light candles. We straighten photos. We gather little trinkets, or brush leaves off gravestones, or place our hands on the earth and whisper, I’m still here. I will always be here.

This is not denial. It’s not unhealthy. It is love, made visible.

Continuing to mother after death is not holding on too tightly. It is holding on rightly—to the truth that love does not end when life does. And so we build our small altars. We tend them as we once tended scraped knees and tangled hair. They are not substitutes. They are sacred spaces where we place the mothering that still lives in us.

And in doing so, we remember: we are not alone in this.

All over the world, in quiet corners and sacred places, other mothers are still mothering too. There are small altars. Sacred shelves. Sun-warmed headstones. Jars of buttons. Half-folded blankets. Unopened birthday cards. There are mothers who tuck notes into the soil, who leave offerings at crash sites, who talk to the sky in whispers only their child would recognize.

We each find our own way. We create places where our mothering can still live. Places where we can do, when so much was taken. Places where we can say, again and again, I remember. I still love you. I always will.

These acts may be quiet. They may be unseen. But they are not small.

They are the threads that keep us tethered—not just to our children, but to ourselves. And to each other.

This is how we keep mothering.